BRIEFING NOTE ON EU STRATEGIC DEPENDENCIES ON CHINA

Since 2020, China overtook the US and became the EU's largest trade partner in terms of goods. However, this intense economic relationship is not equal and implies European dependencies, especially regarding the export market, outbound investments, supply chains, and critical inputs.

The European Commission has therefore published a report that aimed at identifying, among these dependencies, those that can be considered as strategic dependencies because of their link to critical economies. It has drawn up a list of foreign-dependent products, which includes 137 products identified as highly dependent such as raw materials or chemicals. Indeed, a part of the materials imported, and especially from China, is highly important in end-use, EU green and digital objectives, or European production capacities. According to this report, the EU is importing 52% of its foreign-dependent products from China. These pre-identified products represent about 6% of the total value of goods imported by the EU[1].

Strategic dependencies on China

The EU determined that some of the identified strategic dependencies that might result into vulnerabilities are the consequences of a strong concentration of global production in China[2].

Critical raw materials

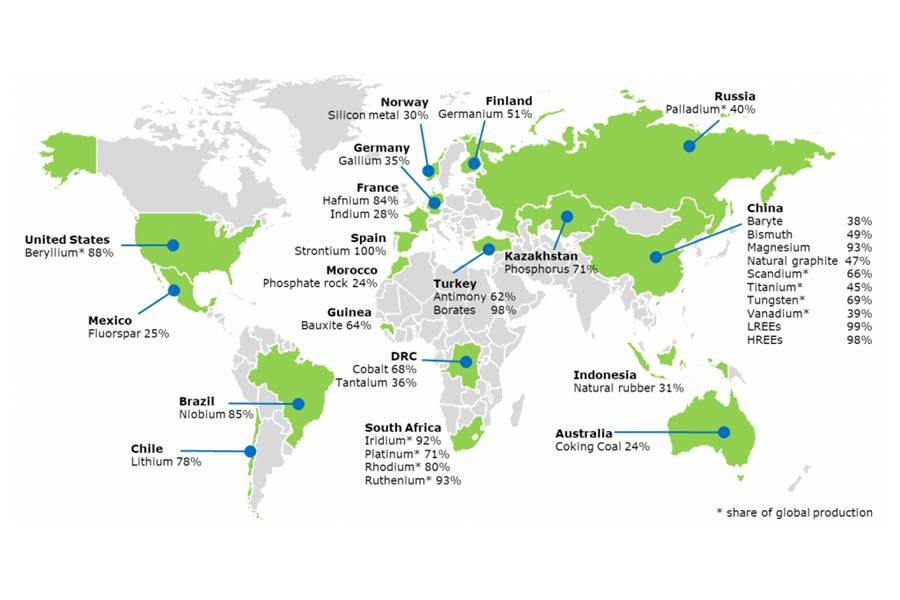

The technological advancements that will determine the EU’s ability to achieve its green and digital transitions are related to its access to critical raw materials (CRM). On this area, the EU is currently facing a lot of dependencies from China (see figure), the largest global CRM producer.

More specifically, rare earths elements (REE), a group of 17 specialty metals (comprising scandium, yttrium and the 15 lanthanides), are particularly important for key products and technologies across a wide range of areas from electronics to power generation, healthcare, space, and defense. For instance, they are used to produce permanent magnets, which are necessary components in electric motors. In fact, the EU is dependent on China, which represents 98% of its imports, and 86% of the global production of REEs[3].

Countries accounting for largest share of EU supply of CRMs

Source: European Commission

Active pharmaceutical ingredients

The EU pharmaceutical supply chain is deeply affected by the production’s concentration of generic active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in India and China, which gather 66% of the global production[4]. Indeed, China holds a share of 45% in the total extra-EU import volumes, that account for 53% of the EU’s total import value of APIs[5].

Chemicals

In this field, six major chemicals were identified as predominant within supply and value chains for the green, digital, and resilient transition, including energy storage, food production, nuclear material production, semi-conductor production, or space missile and rocket nozzle production.

Here, China is the main EU supplier for about 25% of the identified chemical products imports[6].

Solar photovoltaic panels and technologies

According to the European Commission, meeting the goals of the European Green Deal implies a threefold increase in solar energy generation by 2030 and an almost tenfold rise by 2050. Furthermore, solar photovoltaic (PV) technologies are critical in light of the EU’s space and defense interests. However, contrary to the wind sector where the EU industry has a strong position, the EU PV industry is more reliant on international supply and value chains.

In this highly important area, China is leading in all steps of the PV manufacturing value chain and represents 63% of the EU imports in 2019[7], which creates a strategic dependence that could impact the EU’s future deployment of solar technologies. Moreover, 54% of the polysilicon production (a key component of solar modules) is located in the Xinjiang region[8], politically sensitive due to suspicions of forced labor by the Uighur minority.

Cybersecurity technologies and capabilities

The recent increase in global tensions, including threats related to cyber-attacks, has raised the need for the EU to strengthen its resilience in cyber field. Nevertheless, the EU remains behind the US and China in cybersecurity innovation and investments[9]. This includes the area of defense, where most hardware and software are developed in the US and manufactured in China. These weaknesses create important concerns in key areas, such as personal data management or defense technologies. This highlights the risks for the EU of becoming reliant on foreign providers to state-of-the-art technologies in these sensitive areas.

Consequences

All these dependencies are exposing the EU to potential export restrictions imposed by third countries, to price hikes, to supply chain disruptions, as well as to risks of shortages. For example, the EU’s reliance on China for the whole rare earths’ value chain leads to emphasize its vulnerability towards China’s ability to set prices.

Conclusion

In a world of growing tensions, the EU needs to strengthen and diversify trade with international partners in order to increase its ability to act autonomously and to reduce its dependence on Chinese strategic importations. Indeed, if some dependencies have been illustrated during the COVID-19 crisis (magnesium, rare earths…), some other were less visible (services, technologies…) but are still representing a risk for EU’s long-term strategic interests in specific areas.

[1] European Commission, EU strategic dependencies and capacities, 2021, p. 23

[2] European Commission, EU strategic dependencies and capacities: second stage of in-depth reviews, 2022, p. 2

[3] European Commission, Study on the EU's list of Critical Raw Materials, 2020, p. 1

[4] European Commission, EU strategic dependencies and capacities, 2021, p. 62

[5] Idem, p. 64

[6] European Commission, EU strategic dependencies and capacities: second stage of in-depth reviews, 2022, p. 32

[7] European Commission, EU strategic dependencies and capacities: second stage of in-depth reviews, 2022, p. 40

[8] U.S. Department of Labor, Traced to Forced Labor: Solar Supply Chains Dependent on Polysilicon from Xinjiang, 2020

[9] European Commission, EU strategic dependencies and capacities: second stage of in-depth reviews, 2022, p. 49